Design a Chat Service

Having spent as much time as I have on front end work, my back end system design skillset is in bad shape. Starting with this post, I will post my solution and thoughts to various system design scenarios.

A Chat System

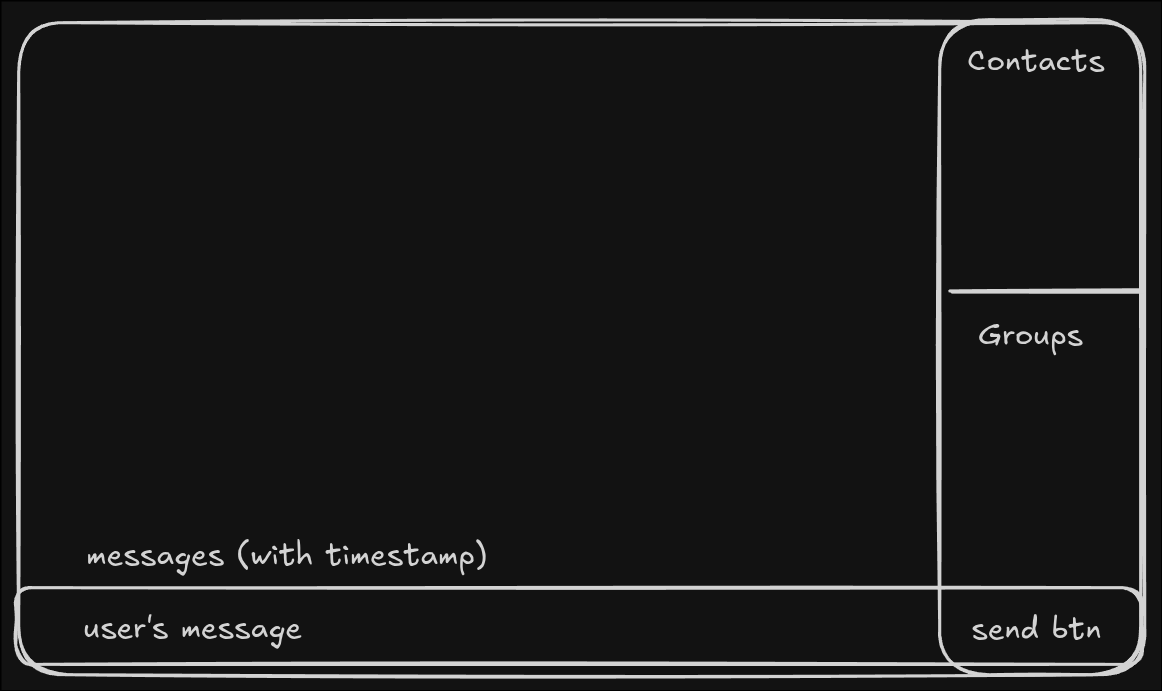

First things first, let’s start with defining what our app should do. Below you’ll notice a crude excalidraw sketch of what a user’s chat experience might look like.

From this sketch, you can already know that we’ll have to support:

- Contacts

- Groups

- Sending messages

- Displaying messages depending on which user or group is clicked.

The CRUD Service

For starters, the bulk of our APIs are going to be relatively simple CRUD operations and basic authentication. We’ll start with these simpler requirements before moving to the more interesting part of creating a plan to scale our chat services. This service is monolithic. Given the limited number of endpoints it exposes, it is convenient to have them live in the same service.

Entities and their APIs

To scale our database, we’ll use the primary + followers scaling pattern. We deploy several copies of our database to distribute read related load among the instances of the database. All write operations are directed at the designated “primary” database. If the primary database goes down, another database is elected the primary to accept writes. This works well for our design because our relational database will handle read-heavy operations unrelated to the chat messages themselves.

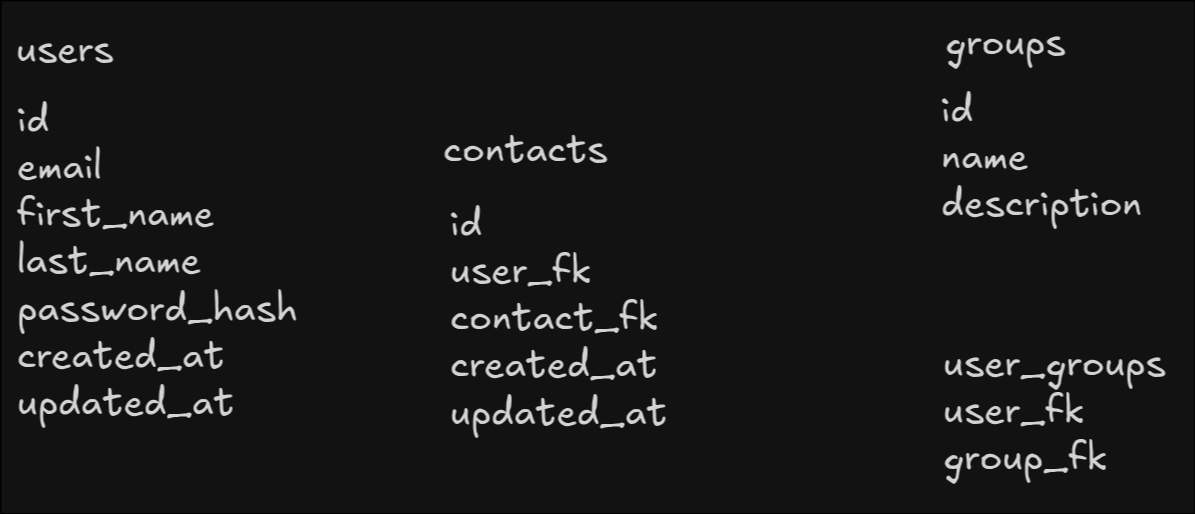

Below is another crude Excalidraw sketch of our entities for our Postgres database. You’ll notice we have users, groups,

contacts, and a junction table for users and groups (user_groups). Storing chat messages will come later in a different

database.

As for endpoints, we really only need to acknowledge they exist as they are basic CRUD endpoints. Here are endpoints we’ll need - It’s possible we’re missing some from the list — which is okay since we don’t need to spend a lot of time talking through the detials of each of these endpoints.

POST /api/v1/signup

POST /api/v1/login

GET /api/v1/me

GET /api/v1/users/{userId}/groups

POST /api/v1/groups

GET /api/v1/groups/{groupId}

GET /api/v1/groups/{groupId}/members

PUT /api/v1/groups/{groupId}

DELETE /api/v1/groups/{groupId}

GET /api/v1/users/{userId}/contacts

GET /api/v1/users/{userId}/contacts/{contactId}

PUT /api/v1/users/{userId}/contacts/{contactId}

DELETE /api/v1/users/{userId}/contacts/{contactId}Great, the CRUD part of our work is done. Let’s look at the chat service itself.

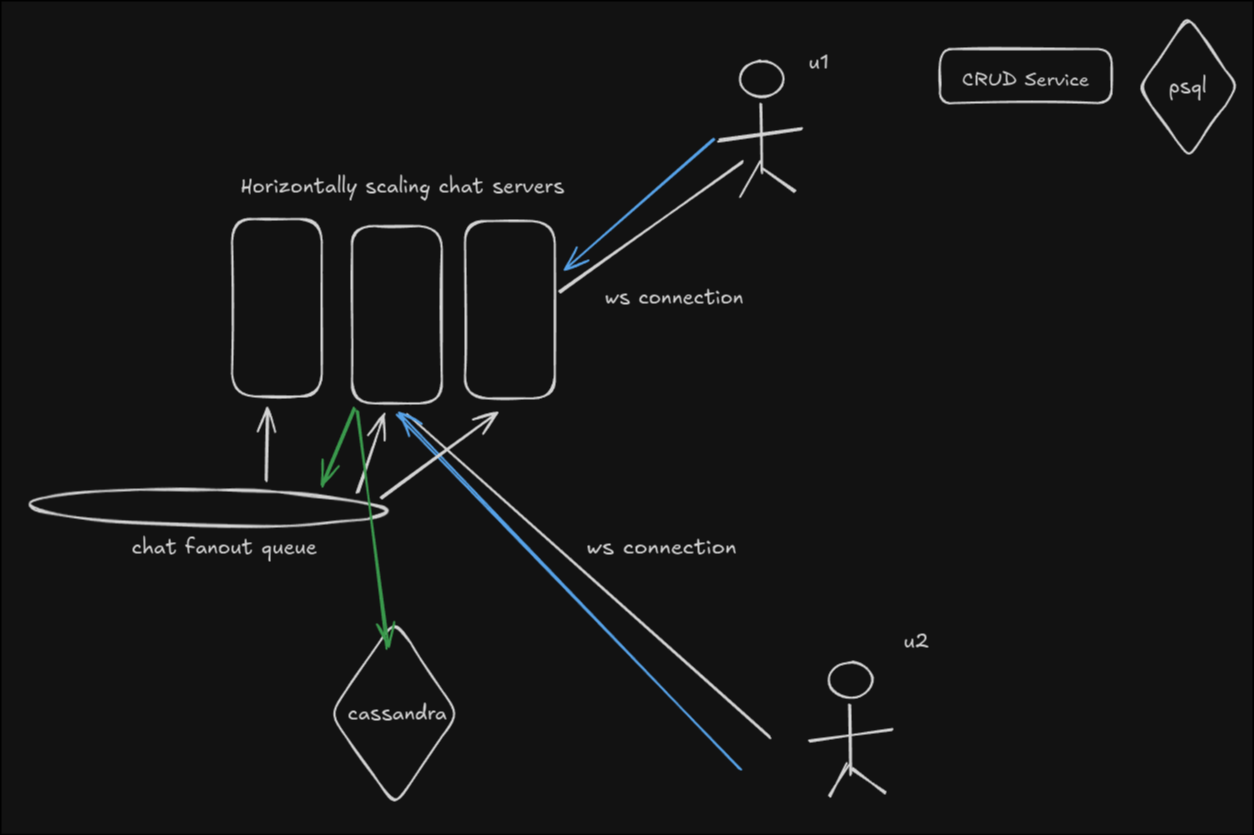

Scaling a Chat Service Iteration 1

At this point, we need to consider how we manage our chat services. The challenges of chat are many, but a couple of important important aspects of our design should address 1) how we scale chat service instances which can be inheritantly stateful and 2) how we store and query large amounts of chat data.

To address the first challenge, Let’s think back to our requirements. We need a system that will support both chatting with an individual and a group. For starters, let’s go with with a design where fanout is acceptable— fanout is especially convenient when some chat messages will be directed at more than one user at a time, and is acceptable at a smaller scale. Therefore, each time a message is sent from one of our chat servers, it will hit many servers — including servers without the target recipient. Let’s accept this up front and move on — (We’ll address this later in attempt 2).

To address the second challenge of storing and retrieving data, we’ll use a non-relational database. Cassandra will suffice for our use case as it is designed to be write heavy and has far fewer scaling constraints than a traditional database. Since we don’t benefit from making extensive use of joins, etc, a database like Cassandra is even more favorable. The composite key for our schema is important here because we want to make sure that we are able to pull records from Cassandra in a way that is ordered by their creation date since a user will generally want their most recent messages to display. For this reason, our composite key is (chat_id, message_id) where the message_id is derived and can be ordered by time.

Our message schema might look something like this:

id: time based id

chat_id: uuid of individual contact or group

kind: 'group' | 'individual'

message: string

timestamp: timeWith a few key decisions described above, let’s outline a high level flow of data and events.

- User logs on.

- User’s groups and contacts are loaded.

- The user is connected to a chat server via websocket. (Generally a server geographically nearby)

- User selects either a contact or group.

- The most recent n messages from the relevant chat are loaded and displayed to the user.

- The user types a message, presses enter, and the message is sent via web socket connection to their chat server.

- The chat server both saves the message to Cassandra and places the message into a message queue that all other chat servers subscribe to.

- Each server will check the users/groups connected on its instance. If the chat_id matches a contact or group ID, the message is sent via web socket connection to that user where the user’s UI maps it to the correct chatroom.

Scaling a Chat Service Iteration 2

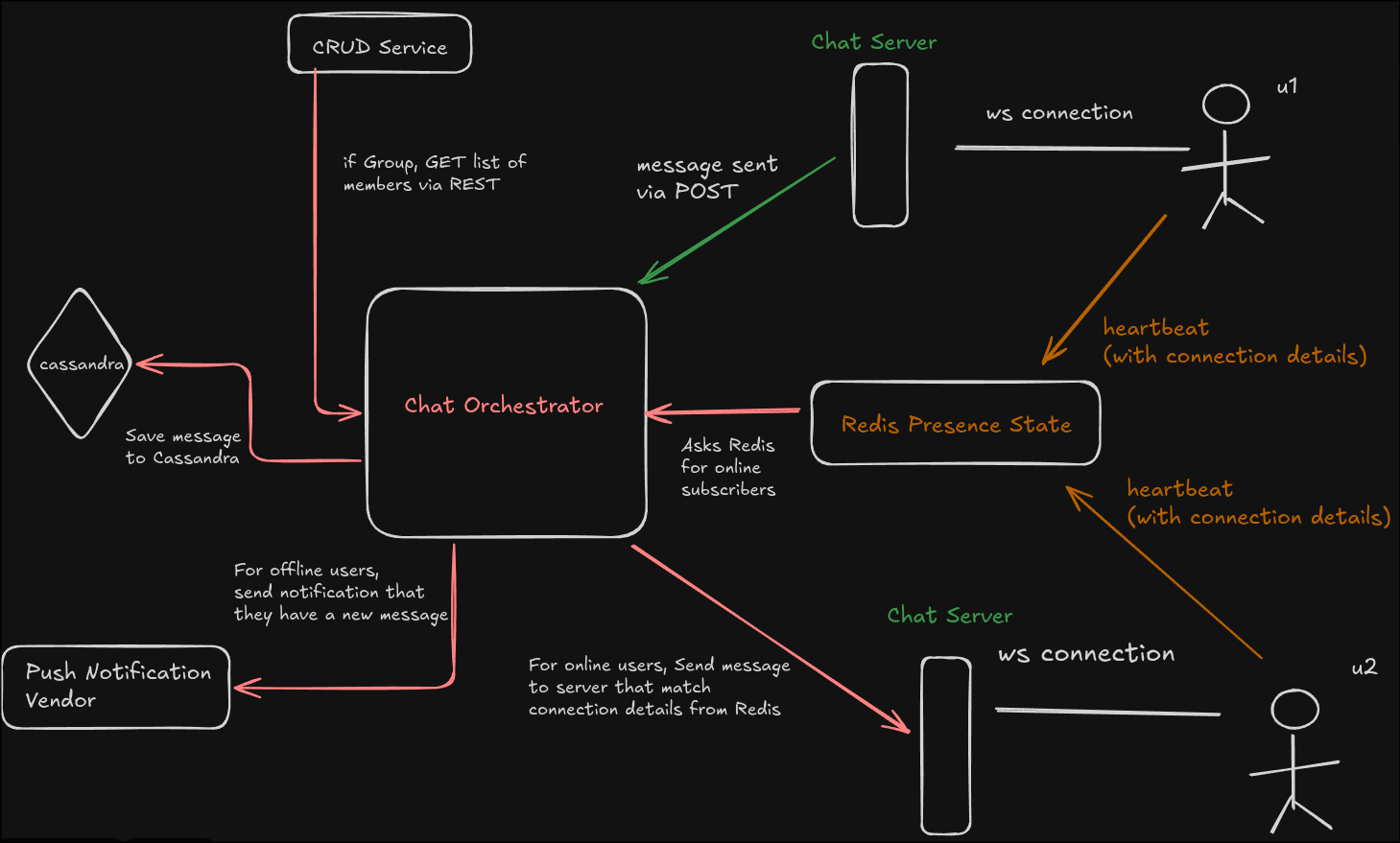

The above chat design generally works but is wasteful as our chat service scales. To improve the performance of our chat design to allow it to better scale, we can tweak the design so that an orchestrator service can properly direct messages only to servers with subscribers. The gist of the design is displayed below.

Let’s talk through what’s happening here.

- Like before, users login and are connected to their chat servers.

- This time, the user pings a heartbeat that ends up in Redis (proxied/authenticated by a server not pictured above)

- Redis’ job is to track the state of online users. Each user entry has a short TTL so they are removed when the heart beat stops. Additionally details about which server a user is connected to is saved in the Redis store.

- When user 1 sends a message to a group user 2 is in, it it sent to their chat server via web socket and forwarded to a chat orchestrator.

- The chat orchestrator’s job is to route messages. It always saves the message to Cassandra before doing additional routing.

- Since user 1 sent a group message, the orchestrator makes a GET request to our CRUD service in order to get all members of the group. (As an aside, we’d likely cache this GET request for speed and scalability).

- The chat orchestrator queries Redis for all users in the Group. Users who are online return values indicating the chat server they are connected to. Users who are not online are do not return any value and the chat service infers they are offline.

- The chat orchestrator sends the message to user 2’s chat server which forwards the message to user 2 via web socket.

- Other users in the group who are offline, receive a notification through a 3rd party notification vendor.

On top of targeted routing of messages to online users, we’ve also added a source of truth for knowledge of online users, and notifications. All in all, the second iteration add some complexity to our chat app, but is more robust and scales smoother in its message routing. We could continue to iterate, but this is where we stop for this blog for now.

Before we conclude, we can go ahead and acknowledge weaknesses in this second iteration that could be addressed in future iterations.

- The biggest weakness is the reliance on a single Redis instance. We could imagine a design that uses a consistent hash ring to scale the Redis instances beyond just a single instance.

- We have not discussed possible strategies for caching and searching chat histories (given Cassandra’s design constraints).

- We haven’t discussed our front end strategy — (i.e. While React is widely adopted, managing long lists of chat message might be come with less friction using another framework)

- We haven’t discussed encryption.

All in all, I’ve learned a lot studying about chat design, and am eager to do more posts like this one in the future for other design topics. Feel free to reach out with feedback. I hope to do another one of these soon.